A Patient with Sequential Diseases of Langerhans Cell Sarcoma, Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis, and Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

-

摘要:

朗格汉斯细胞组织细胞增生症(LCH)和朗格汉斯细胞肉瘤(LCS) 的特征是朗格汉斯型细胞的克隆增殖,可能与急性T淋巴细胞白血病(T-ALL) 和其他淋巴肿瘤同时或相继发生。一例15岁女性患者被诊断为T-ALL,在维持化疗期间出现多系统LCH,化疗好转后又出现病情进展,且对二线化疗耐药。由于患者存在KRAS基因的c.G35A (p.G12D)突变,加用曲美替尼靶向治疗,效果显著,治疗一周达部分缓解。治疗3个月后再次出现颈部淋巴结肿大,病理诊断为LCS,7 d内患者病情急速进展,最终死亡。上述三种疾病进展及演变可能与转分化、克隆演化及化疗药物等因素有关。靶向药物在短期内可能存在一定疗效。

-

关键词:

- 朗格汉斯细胞组织细胞增生症 /

- 朗格汉斯细胞肉瘤 /

- 急性T淋巴细胞白血病 /

- 克隆演变 /

- 靶向治疗

Abstract:Langerhans cell histiocytosis(LCH)and Langerhans cell sarcoma(LCS)are characterized by clone proliferation of Langerhans-type cells, which may occur concurrently or sequentially with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) and other Lymphoid neoplasms. A 15-year old female patient diagnosed with T-ALL developed LCH involving multiple systems during maintenance chemotherapy of T-AL. After treated with chemotherapy with improved result, the patient showed progression of the illness and refractory to the second-line treatment. We found c.G35A (p.G12D)mutation in the KRAS gene and used the targeted drug Trametinib for treatment. The treatment proved effective, leading to partial remission within a week. Three months after Trametinib treatment, the patient developed new lymphadenopathy. Biopsy revealed the existence of LCS. The disease progressed quickly, and the patient died 7 days after diagnosis of LCS. The case of patients with T-ALL then developing LCH and LCS sequentially is extraordinarily rare. The causes of the case is unclear and may be related to cell transdifferentiation, clonal evolution, and chemotherapy. Targeted drugs can contain this disease for a short time.

-

倪鑫

北京儿童医院 院长

《罕见病研究》副主编

全球罕见病患者已达2.63~4.46亿,数之众堪比大国。Orphanet数据库中,5018种罕见病记录显示,儿童是罕见病主群体:3510种仅在儿童期发病,占56.9%;908种从儿童期到成年期皆可发病,占14.7%;600种仅在成年期发病,占9.7%。罕见病通常影响多器官系统,病程呈慢性、进行性、耗竭性,最终造成残疾甚而危及生命。罕见病患儿中约30%无法等到庆祝自己的5岁生日。由于罕见病药物研发风险大,常使研发者望而却步,因此,罕见病用药也称为孤儿药。令人欣喜的是,近年来我国多部门陆续出台多项相关政策,积极推进全国罕见病诊疗协作网及救助体系的建立等“中国模式”的探索,让罕见病儿童看到了从容生存的希望;也让从事罕见病的临床和科研工作者感到了如山的依靠,重燃对罕见病的诊治热情而投入无涯的研究!

儿科是罕见病患者救治的主战场,儿科医师是推动我国罕见病规范诊疗的主力军。儿科医师需要密切追踪国内外罕见病领域研究前沿,不断学习罕见病诊疗,开展案例交流。深入研究罕见病要从认识疾病开始,进而及早诊断、规范治疗、系统随访。然而,因疾病罕见而造成认识不足,漏诊、误诊其实难免。《罕见病研究》杂志搭建了优秀的交流学习平台,在拥有丰富经验的多学科专家共同参与下,将该杂志打造成“罕见病诊治新知的给养站”。孤儿药的研发和使用经验在此分享,使之成为医师汲取“罕见病新药体验的滋养泉”。医者大智,乐于攀登高峰;郎中普仁,共享学海浩瀚。不仅使罕见病诊疗研究推至新高度,更重要的是释放患儿的救治困窘,使他们获得从容的人生。

本期为儿童罕见病专刊,内容丰富新颖,栏目设置包括述评、专家笔谈、论著、指南与共识、诊疗方案、病例报告、孤儿药专栏和综述等,系统阐述了儿童罕见病的诊治现状及相关精准治疗的探索,对于儿童罕见肾脏病、自身炎症性疾病、Blau综合征、Alport综合征、高免疫球蛋白E综合征、罕见综合征耳聋及戈谢病等多种疾病的临床特征、诊断和治疗进展等进行了分析和总结,展示了青少年女性ROSAH综合征的多学科病例讨论,且有多例儿童罕见病的病例报告分享。籍以此专刊的出版,对全国范围内从事儿童罕见病的医师提供临床参考,更好地为广大患儿服务。

生命若是旅行,感恩是最美的绽放,成全千回百转的温暖。智者乐山山如画,仁者乐水水无涯。让我们共同为罕见病儿童从容的未来努力!

2022年7月

作者贡献:论文选题与设计:王天有、张蕊;论文整合与修订:王天有、张蕊、李志刚;撰稿:田宇、王冬、魏昂、杨颖、张利平;临床诊治及数据收集:马宏浩、王婵娟、崔蕾。利益冲突:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。 -

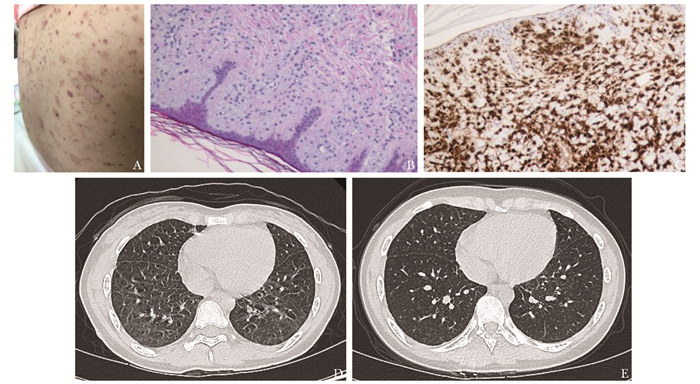

图 1 患者皮肤、皮肤组织病理学及肺部影像学变化

A.患者入院前1个月皮疹情况,全身皮肤遍布红色及棕黄色斑丘疹,部分破溃、结痂,部分色素脱失,可见散在皮疹沉着(此图由家长提供);B.左前臂皮肤组织活检,HE×200;C.左前臂皮肤组织活检,CD1a,免疫化学染色,×200;D.入院评估时肺CT图像,两肺可见数处薄壁气腔,考虑为朗格汉斯细胞组织细胞增生症(LCH)肺内改变;E.中等剂量克拉屈滨(2-CDA)联合阿糖胞苷(Ara-C)方案化疗3个疗程后评估肺CT图像,两肺可见数处薄壁气腔,考虑为LCH肺内改变,较前有所缩小、减少

Figure 1. Skin, histological and immunohistochemical staining findings of skin and changes of scanning in chest of the patient

图 2 患者单用Ara-C化疗期间皮肤、皮肤组织病理学及肺部影像学变化

A.右腋下淋巴结组织活检,HE×200;B.背部、四肢新发皮疹;C.肺CT:两肺小条样间质浸润合并数处薄壁气腔,考虑为LCH肺内改变,较前有所增大;D.骨髓活检,HE×400;E.骨髓活检,CD1a,免疫化学染色,×400;F.加用靶向治疗后,两肺小条样间质浸润合并数处薄壁气腔,考虑为LCH肺内改变,较前有所缩小、减少

Figure 2. Skin, histological and immunohistochemical staining findings of skin and changes of scanning in chest of the patient during chemotherapy with Ara-C

表 1 基因突变分析结果

Table 1 Genomic analysis of the patient

基因 转录本 外显子 核苷酸变异 氨基酸变异 变异类型 变异丰度(%) KRAS NM_004985 exon2 c.35G>A p.G12D SNV 45.00 BRAF NM_004333 exon15 c.1742A>T p.N581I SNV 18.75 RAF1 NM_002880 exon7 c.770C>T p.S257L SNV 14.00 FGF4 NM_002007 exon1 c.302A>C p.D101A SNV 9.86 RB1 NM_000321 exon1 c.34A>C p.T12P SNV 5.17 FOXL2 NM_023067 exon1 c.734T>G p.V245G SNV 6.82 FAT4 NM_001291303 exon1 c.1298C>T p.S433F SNV 21.57 IKZF1 NM_006060 exon6 c.656A>G p.H219R SNV 32.20 NOTCH1 扩增 2.00 SNV:单核苷酸变异 表 2 存在T-ALL后出现LCH和/或LCH后出现LCS患者总结

Table 2 Summary of patients with LCH following T-ALL and/or LCS following LCH

患者编号# 参考文献 性别/年龄(岁) 诊断1(部位) 治疗1 间隔时间(月) 诊断2(部位) 治疗2 预后 1 [3] 男/5 T-ALL 化疗 31 LCH(阴茎) 化疗+手术切除 存活 2 [3] 女/5 T-ALL 化疗 33 LCH(皮肤) 手术切除 存活 3 [5] 男/5 T-ALL 化疗 7 LCH(皮肤、骨髓) 化疗 死亡(LCH诊断6周后) 4 [6] 男/4 T-ALL 化疗 0 LCH(皮肤、肺、肝、脾) 化疗 死亡(LCH诊断8月后) 5 [7] 男/7 T-ALL 化疗 22 LCH(皮肤、肺) 化疗 死亡(LCH诊断13周后) 6 [10] 男/34 LCH(肺) 戒烟 12 LCS(肺) 手术切除 存活 7 [11] 男/41 LCH(淋巴结) 手术切除 11 LCS(淋巴结) 化疗 存活 8 [12] 男/73 LCH(皮肤、骨) 手术切除+化疗 0 LCS(肺、消化道) 化疗+手术切除 死亡(LCS诊断17月后) 9a [8] 女/3 T-ALL 化疗 18 LCH(皮肤) 化疗 存活 9b [8] 女/4 LCH(皮肤) 化疗 12 LCS 化疗 死亡 10a [9] 男/8 T-ALL 化疗 24 LCH(皮肤) 化疗 存活 10b [9] 男/10 LCH(皮肤) 化疗 12 LCS(多系统) 化疗 全身转移 11a* - 女/10 T-ALL 化疗 36 LCH(皮肤、甲状腺、颈部淋巴结、胸腺) 化疗+靶向治疗 存活 11b* - 女/13 LCH(皮肤、甲状腺、颈部淋巴结、胸腺) 化疗+靶向治疗 34 LCS(多系统) 靶向治疗 死亡 *11为本例患者;a、b.同一例患者的病情发展的不同阶段;T-ALL:急性T淋巴细胞白血病 -

[1] Gao C, Zhao XX, Li WJ, et al. Clinical features, early treatment responses, and outcomes of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia in China with or without specific fusion transcripts: a single institutional study of 1, 004 patients[J]. Am J Hematol, 2012, 87: 1022-1027. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23307

[2] Egeler RM, Neglia JP, Aricò M, et al. The relation of Langerhans cell histiocytosis to acute leukemia, lymphomas, and other solid tumors. The LCH-Malignancy Study Group of the Histiocyte Society[J]. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am, 1998, 12: 369-378. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8588(05)70516-5

[3] Trebo MM, Attarbaschi A, Mann G, et al. Histiocytosis following T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a BFM study[J]. Leuk Lymphoma, 2005, 46: 1735-1741. doi: 10.1080/10428190500160017

[4] Sabattini E, Bacci F, Sagramoso C, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues in 2008: an overview[J]. Pathologica, 2010, 102: 83-87.

[5] Chiles LR, Christian MM, McCoy DK, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in a child while in remission for acute lymphocytic leukemia[J]. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2001, 45: S233-S234. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.104964

[6] Aubert-Wastiaux H, Barbarot S, Mechinaud F, et al. Childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis associated with T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia[J]. Eur J Dermatol, 2011, 21: 109-110. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.1168

[7] Yokokawa Y, Taki T, Chinen Y, et al. Unique clonal relationship between T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and subsequent Langerhans cell histiocytosis with TCR rearrangement and NOTCH1 mutation[J]. Genes Chromosomes Cancer, 2015, 54: 409-417. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22252

[8] Rodig SJ, Payne EG, Degar BA, et al. Aggressive Langerhans cell histiocytosis following T-ALL: clonally related neoplasms with persistent expression of constitutively active NOTCH1[J]. Am J Hematol, 2008, 83: 116-121. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21044

[9] Castro EC, Blazquez C, Boyd J, et al. Clinicopathologic features of histiocytic lesions following ALL, with a review of the literature[J]. Pediatr Dev Pathol, 2010, 13: 225-237. doi: 10.2350/09-03-0622-OA.1

[10] Lee JS, Ko GH, Kim HC, et al. Langerhans cell sarcoma arising from Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report[J]. J Korean Med Sci, 2006, 21: 577-580. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.3.577

[11] Yi W, Chen WY, Yang TX, et al. Langerhans cell sarcoma arising from antecedent langerhans cell histiocytosis: a case report[J]. Medicine(Baltimore), 2019, 98: e14531.

[12] Kim SW, Choi MK, Han HS, et al. A case of pulmonary Langerhans cell sarcoma simultaneously diagnosed with cutaneous Langerhans cell histiocytosis studied by whole-exome sequencing[J]. Acta Haematol, 2017, 138: 24-30. doi: 10.1159/000476026

[13] Feldman AL, Berthold F, Arceci RJ, et al. Clonal relationship between precursor T-lymphoblastic leukaemia/lymphoma and Langerhans-cell histiocytosis[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2005, 6: 435-437. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70211-4

[14] Ratei R, Hummel M, Anagnostopoulos I, et al. Common clonal origin of an acute B-lymphoblastic leukemia and a Langerhans' cell sarcoma: evidence for hematopoietic plasticity[J]. Haematologica, 2010, 95: 1461-1466. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.021212

[15] Kimura S, Seki M, Yoshida K, et al. NOTCH1 pathway activating mutations and clonal evolution in pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia[J]. Cancer Sci, 2019, 110: 784-794. doi: 10.1111/cas.13859

[16] Kato M, Seki M, Yoshida K, et al. Genomic analysis of clonal origin of Langerhans cell histiocytosis following acute lymphoblastic leukaemia[J]. Br J Haematol, 2016, 175: 169-172. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13841

[17] Choi SM, Andea AA, Wang M, et al. KRAS mutation in secondary malignant histiocytosis arising from low grade follicular lymphoma[J]. Diagn Pathol, 2018, 13: 78. doi: 10.1186/s13000-018-0758-0

[18] Egeler RM, Katewa S, Leenen PJ, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a neoplasm and consequently its recurrence is a relapse: in memory of Bob Arceci[J]. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 2016, 63: 1704-1712. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26104

[19] Ansari J, Naqash AR, Munker R, et al. Histiocytic sarcoma as a secondary malignancy: pathobiology, diagnosis, and treatment[J]. Eur J Haematol, 2016, 97: 9-16. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12755

[20] Ibragimova MK, Tsyganov MM, Litviakov NV. Natural and chemotherapy-induced clonal evolution of tumors[J]. Biochemistry (Mosc), 2017, 82: 413-425. doi: 10.1134/S0006297917040022

[21] Wong TN, Ramsingh G, Young AL, et al. Role of TP53 mutations in the origin and evolution of therapy-related acute myeloid leukaemia[J]. Nature, 2015, 518: 552-555. doi: 10.1038/nature13968

作者投稿

作者投稿 专家审稿

专家审稿 编辑办公

编辑办公 主编办公

主编办公

下载:

下载: